When you think of pyramids, which is the first place you think of? I bet it would be the pyramids of Giza in Egypt. Actually, I won’t hold thinking of the Egyptian pyramids against you. They are, after all, one of the seven wonders of the ancient world. Much like the Egyptians, their southern neighbours—the Sudanese—have their own pyramids scattered all over the country too. In fact, Sudan actually has twice as many pyramids as Egypt. The ancient pyramids of Giza were built somewhere between 2580 to 2560 BC, whereas the pyramids in Sudan were built only around 800 years later.

I went to Sudan in December 2018 to spend Christmas break with my family, arriving in Khartoum with very little idea about what to expect.

break with my family, arriving in Khartoum with very little idea about what to expect.

Khartoum is dry, hot and prone to dusty winds. But unique to it is the fact that there are two river Niles running through it—the Blue Nile and the White Nile. Khartoum is also home to one of the best museums I have ever been to in my life. You can spend unending hours soaking in the history of thousand of years at the National Museum of Sudan, for a fee of only 10 Sudanese pounds (about 25 cents). The museum, where excavated historical artefacts from different periods are displayed, gives you an overview of the history of the country.

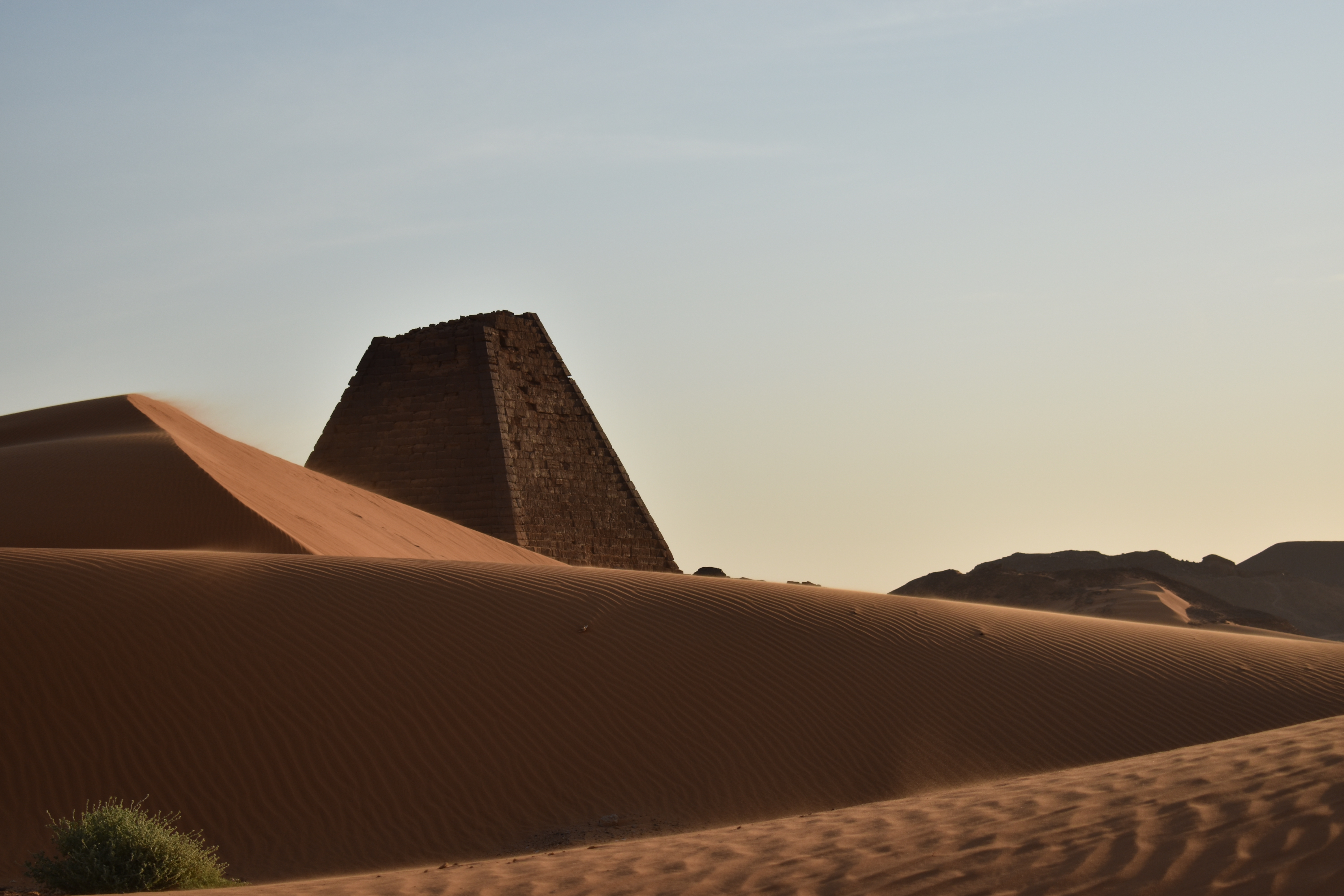

If you head around 200 km north of the capital city of Khartoum, you will find pyramids in the ancient city of Merowe. The Merowite pyramids are much shorter, narrower and have a smaller base compared to the pyramids of Giza. The pyramid complex has since been restored as best as possible by the government of Sudan and hosts tourists each year for guided tours around the pyramids. Some of the pyramids are accessible and you can see the artwork inscribed thousands of years ago on their walls close up. Made using sun-dried mud bricks, in a similar style to their Egyptian counterparts, these ancient pyramids stood in the region of Merowe well after their builders perished.

If you head around 200 km north of the capital city of Khartoum, you will find pyramids in the ancient city of Merowe. The Merowite pyramids are much shorter, narrower and have a smaller base compared to the pyramids of Giza. The pyramid complex has since been restored as best as possible by the government of Sudan and hosts tourists each year for guided tours around the pyramids. Some of the pyramids are accessible and you can see the artwork inscribed thousands of years ago on their walls close up. Made using sun-dried mud bricks, in a similar style to their Egyptian counterparts, these ancient pyramids stood in the region of Merowe well after their builders perished.

Until the 1830s, when Giuseppe Ferlini, an Italian thief, and his wife blew up the tip of 40 such pyramids in Merowe in search of the riches buried within them. Having destroyed much of the structure of the pyramids, Ferlini found treasure in only one of them. He then smuggled these stolen treasures back to Europe and tried to sell them to several European countries. However, many of the prospective buyers he approached believed the gold he found was of inferior quality, similar to the kind found in Egypt at the time, and refused to buy it from him. Ferlini finally sold the jewels for very little money. Today, these treasures sit in museums in Berlin and Munich where Sudanese people have to pay entrance fees see treasures stolen from them by a European man.

When I travel across certain parts of the world like Sudan, I can’t help but reflect on the unfair history of the world and feel agitated. The history of the pyramids in Sudan is same as the history in parts of Mexico, in Nigeria, in the Indian subcontinent, and in many other parts of the world. A European man decided that something in each of these places was of no value to him and as such destroyed it, by proxy erasing parts of the country’s history and robbing a part of its identity. In many of these cases, these stolen treasures are now displayed in expensive museums in European cities where citizens of the original countries will have to jump through hoops, pay to apply for a visa—which, if granted—would still mean having to pay for a flight ticket which many can’t afford, followed by an expensive museum ticket to see treasures stolen from them by white supremacists. Most recently, the British Museum agreed to ‘loan’ Nigeria the exhibits of the artefacts it looted from the Kingdom of Benin 120 years ago. I face this ethical dilemma when I visit museums and see artefacts stolen from all over the world—the money I pay as a ticket should actually go to the countries where these artefacts were looted from. It makes me wonder if such a time will come when these stolen artefacts will be returned to the countries they were stolen from.

When I travel across certain parts of the world like Sudan, I can’t help but reflect on the unfair history of the world and feel agitated. The history of the pyramids in Sudan is same as the history in parts of Mexico, in Nigeria, in the Indian subcontinent, and in many other parts of the world. A European man decided that something in each of these places was of no value to him and as such destroyed it, by proxy erasing parts of the country’s history and robbing a part of its identity. In many of these cases, these stolen treasures are now displayed in expensive museums in European cities where citizens of the original countries will have to jump through hoops, pay to apply for a visa—which, if granted—would still mean having to pay for a flight ticket which many can’t afford, followed by an expensive museum ticket to see treasures stolen from them by white supremacists. Most recently, the British Museum agreed to ‘loan’ Nigeria the exhibits of the artefacts it looted from the Kingdom of Benin 120 years ago. I face this ethical dilemma when I visit museums and see artefacts stolen from all over the world—the money I pay as a ticket should actually go to the countries where these artefacts were looted from. It makes me wonder if such a time will come when these stolen artefacts will be returned to the countries they were stolen from.

Maliha Fairooz is a 28-year-old Bangladeshi solo traveller, who has travelled to 84 countries, on a Bangladeshi passport. Through her blog www.maliharoundtheworld.comshe shares her experience of travelling as a brown, Muslim, Bangladeshi woman while simultaneously encouraging a culture of travel amongst Bangladeshi youth.